ISSUE OVERVIEW

Parole is a form of behavioral incentive by which incarcerated men and women may be considered for supervised release before the end of their indeterminate prison sentence.[i] Often used in conjunction with or instead of good time and earned time credit policies, parole has been employed by the American criminal justice system since the mid-19th century.[ii] By the 1940s, every state in the U.S. had some form of parole or release incentive credits to respond to overcrowding and achieve rehabilitative goals.[iii]

Criminal penalties became the focus of national attention in the so-called “Truth in Sentencing” movement of the 1980s and early 1990s, with the aim of ensuring greater severity in sentencing and certainty of the total time ultimately served. Across the country, jurisdictions enacted harsher sentencing guidelines, including the widespread use of mandatory minimums.[iv] Simultaneously, nearly a dozen states and the federal government abolished parole, while virtually every jurisdiction reduced eligibility for parole and other release incentive programs.[v] Consequently, the number of people released directly from prison to the community without supervision increased 119% over the next 20 years.[vi] Since the early 2000s, however, nearly half of all states have begun to reform their parole policies or have otherwise expanded release incentive programs.[vii]

Parole considerations are typically overseen by a governor-appointed board and often are confirmed by a state’s legislative branch.[viii] Parole boards weigh several factors, often determined by the legislature, to determine a person’s rehabilitative progress. These factors generally include the nature of the offense committed, criminal history, a risk and needs assessment, participation in programming during incarceration, and release plans.[ix] Fewer than 10 states require that the full parole board meet in person with the eligible party before making a release determination.[x] Parole boards are typically responsible to report the number of grants and denials made within a year.

States vary in the percentage of time that must be served prior to parole eligibility. The average minimum requirement across states is 33%.[xi] Most states have adopted a percentage structure based on offense type or class. Conversely, Nebraska prisoners are eligible for parole after serving 50% of their time, regardless of their offense.

Research is now beginning to show that those released to parole supervision have lower recidivism rates than those who complete their sentence in prison.[xii] Findings from one state demonstrated a 36% lower likelihood of reincarceration among those released to parole than their peers who stayed in prison, predicting better outcomes despite controlling for risk factors that would otherwise foretell recidivism.[xiii] Robust research also shows that in-prison programming aligned to individual risks and needs can contribute to safer and more constructive prison environments, lower recidivism rates, higher employment attainment post-release, and overall cost savings to the correctional agency.[xiv] This remains true when program participation is incentivized by policies like parole and earned time credits.[xv] In contrast, data indicates that determinate sentencing contributes to increases in prison misconduct. [xvi]

Policies like parole that incentivize rehabilitation may also be preferred by crime survivors. Polling demonstrates that 6 in 10 victims prefer shorter prison sentences and more spending on prevention and rehabilitation, as opposed to prison sentences that keep people in prison for as long as possible.[xvii] By a 2-to-1 margin, “victims prefer that the criminal justice system focus more on rehabilitating people who commit crimes than punishing them.”[xviii] The same margin applied when victims were asked about investment in community supervision, such as probation and parole, versus more investment in prisons and jails.[xix]

POSITION STATEMENT

While crime often harms direct victims, it also tears at the fabric of society and results in a breach of community trust. The person responsible for a crime must be held accountable for the harm caused, and the public must be protected. When someone is convicted of a crime, a just penalty should take into account the nature of the offense and the extent of harm caused. Alternatives to incarceration should be prioritized and the use of imprisonment limited to instances where proportionality and safety concerns require incapacitation.

If incarceration is required, an indeterminate sentence that offers parole, earned time credits, and good time credits in a complementary manner can best serve the punitive goals of incarceration, while cultivating rehabilitation and providing a pathway to earn back community trust. Victims should have assurance that a set term of incarceration will be served before parole or other release incentives become available. Victims must also receive clear communication at sentencing regarding the earliest possible release date and notification when the release date approaches.

Release incentives should be available for at least 50% of the court-imposed sentence. This period may begin with discretionary parole eligibility, but good time credits and earned time credits should be available to accrue during a portion of this parole-eligible period. This process both offers hope to men and women behind bars and instills an expectation that making amends and earning back community trust are foundational to accountability.[xx] The same percentage of time served prior to eligibility for release incentive programs should apply regardless of offense type or classification. This affirms that consideration of the nature of the offense is reserved to the sentencing judge, while preserving the distinct purpose of parole’s focus on rehabilitation and reentry readiness.

Making parole available alongside the opportunity to gain earned and good time credits creates a complementary structure that helps to incentivize the behavior considered in parole determinations. A greater proportion of time should be awarded for earned time relative to good time, placing higher value on rewarding positive behavior than simply avoiding misconduct. Further, earned time should not be reserved to a small subset of programs, but rather should be made equally available for completing a wide variety of programs and activities. This should include faith-based programs that prepare incarcerated people to live as good citizens and provide them opportunities to practice positive behaviors.

Parole boards should include members of the community at large, corrections professionals, victims, and people who themselves have successfully reintegrated into the community after incarceration. Determinations of release should focus on evaluation of rehabilitative progress and character development. When parole boards deny release, they should provide the incarcerated person with a written decision documenting the reason for the denial and expected steps for remediation. All who are nearing release through parole or credit programs or at the end of their sentence ought to receive some supervision and support for the initial period of reintegration. Conditions for supervision ought to be narrowly tailored to the unique risks and needs of the individual and track metrics of success.

As a result of making parole, earned time, and good time credits available in this manner, we ensure proportional punishment is served while also installing a pathway to redemption that requires active and intentional effort by the incarcerated person. This approach can result in more restorative outcomes for all involved, including greater overall victim satisfaction levels, more constructive prison culture, and increased public safety benefits, while reducing prison overcrowding and the related taxpayer burden.

RESOURCES

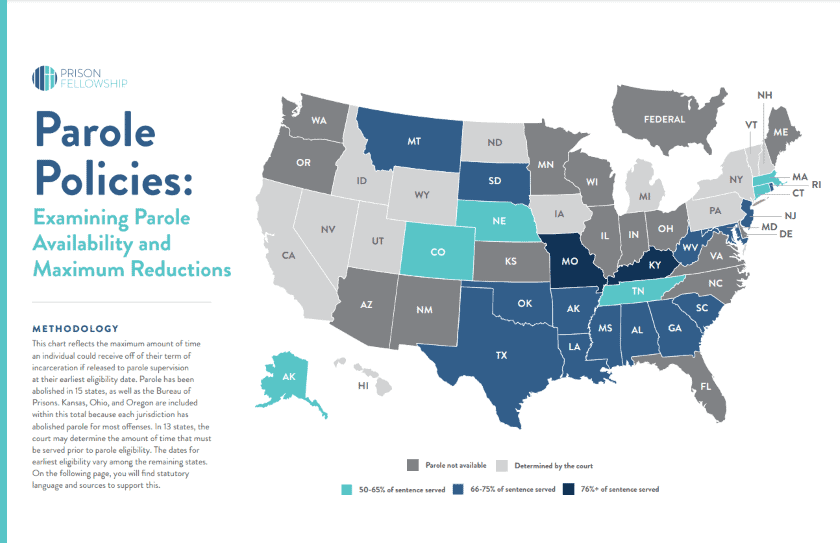

PAROLE POLICIES: EXAMINING PAROLE AVAILABILITY AND MAXIMUM REDUCTIONS

This chart reflects the maximum amount of time an individual could receive off of their term of incarceration if released to parole supervision at their earliest eligibility date. Parole has been abolished in 15 states, as well as the Bureau of Prisons.

[i] Historically, American terms of incarceration were “determinate,” meaning for a set period of time that must be served to completion. Indeterminate sentencing generally sets both a total sentence length and an earliest release date, subject to good or earned time credits or release to parole supervision. Catie Clark, et al., Assessing the Impact of Post-Release Community Supervision on Post-Release Recidivism and Employment, U.S. Department of Justice (2016), https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/249844.pdf.

[ii] American Law and Legal Information, Probation and Parole: History, Goals, and Decision-Making, Law Library- American Law and Legal Information (2020), https://law.jrank.org/pages/1817/Probation-Parole-History-Goals-Decision-Making-Origins-probation-parole.html.

[iii] Id.

[iv] Nancy Gertner, A Short History of American Sentencing, 100 J. Crim. L. & Criminology, 691, 700 (2010),https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7361&;amp;context=jclc.

[v] Katherine Rosich & Kamala Mallik Kane, Truth in Sentencing and State Sentencing Practices, National Institute of Justice (2005), https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/truth-sentencing-and-state-sentencing-practices.

[vi] Pew, Max Out: The Rise in Prison Inmates Released Without Supervision, Pew Charitable Trusts (2014), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2014/06/04/max-out.

[vii] The Supreme Court has held that traditional due process protections do not extend to those eligible for parole. Legal Information Institute, The Procedure that is Due Process, Cornell Law School (2020), https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/amendment-14/section-1/the-procedure-that-is-due-process.

[viii] American Law and Legal Information, supra note i.

[ix] Id.

[x] Id.

[xi] The average amount of time required to be served prior to parole eligibility is 33%. Most generous state: MO (15%) Most stingy state: 6 state tie between AK, CO, CT, MA, NE, & TN) at 50%. Fourteen states lack a specific percentage of time served before parole eligibility vests. Thirteen of these states reserve this authority for the court, while in HI it is set by the parole board.

[xii] Pew, supra note v; Alison Lawrence, Cutting Corrections Costs: Earned Time Policies for State Prisoners, National Conference of State Legislatures (2009), https://www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Documents/cj/Earned_time_report.pdf.

[xiii] Id.

[xiv] Grant Duwe, The Use and Impact of Correctional Programming for Inmates on Pre- and Post-Release Outcomes, National Institute of Justice (2017), https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/250476.pdf.

[xv] Lawrence, supra note xi.

[xvi] William Bales & Courtenay Miller, The Impact of Determinate Sentencing on Prisoner Misconduct, 40 J. Crim. Just. 394 (2012), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047235212000839.

[xvii] ASJ, Crime Survivors Speak, Alliance for Safety & Justice (2016), https://allianceforsafetyandjustice.org/crimesurvivorsspeak/.

[xviii] Id.

[xix] Id.

[xx] The recommended proportions for parole and time credits here assumes the jurisdiction’s sentencing scheme reflects proportional punishments.