Jon Kelly is walking on eggshells. “What’s the point of freeing men and women if we restrict them so much that they can’t be productive?”

Jon Kelly is walking on eggshells. “What’s the point of freeing men and women if we restrict them so much that they can’t be productive?”

Parole and credit policies can ensure proportional punishment is served while also offering an active and intentional pathway to redemption.

Hope Events are one of the backbones of Prison Fellowship’s ministry—but the idea came from a corrections and civil rights leader.

For many people who have spent time in prison, the most difficult barrier to overcome after release is the reentry into employment. In many instances, employers stop reading an application as soon as they see that someone has a criminal record.

Art Hallett was the only one in his teenage group of friends who was never arrested. He credits it to his mother wisely pushing him to enlist in the Air Force at age 17. But his freedom doesn't mean he has never been to prison.

Teshauna experienced the impact that Angel Tree® has on families with incarcerated parents firsthand. Her father was in prison, and the experience was difficult for Teshauna and her family. But Angel Tree stepped in and helped.

Read More

Photo Credit: David Leventi Photography

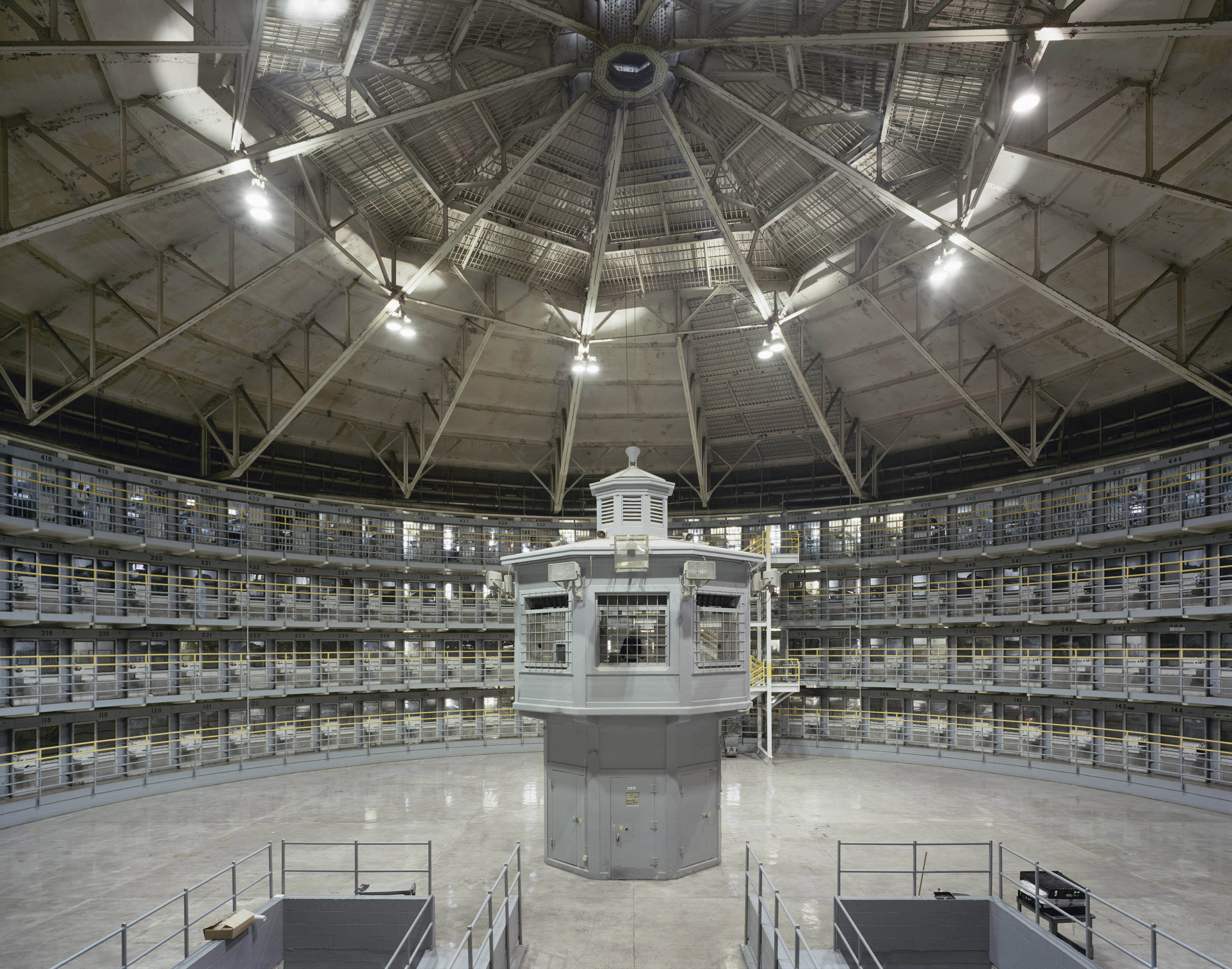

Sitting in the circular center of Stateville Correctional Center’s F House, a lone watchman gave prisoners the sense that they were all being watched at once.

Built in Joliet, Illinois, in 1922, the infamous roundhouse ranks as one of the oldest and costliest in the state.

Members of the tour: (Clockwise, from left) Jacob Moore, Mary Johnson, Arthur Hallett, Brian Ganhs, Charleston Day, and Sonnie Day

This past February, Prison Fellowship celebrated Black History Month with a tour of African American artists who led an evangelism campaign in Illinois.

Daniel Geiter spent much of his young adult years in and out of correctional facilities in and around Chicago. Between his adolescent years and the age of 25, Geiter estimates that he was incarcerated in excess of 20 times.

It was during one of these prison stays that Geiter concluded that things needed to change.

For men and women who have committed crimes, the biggest challenge often isn’t being incarcerated—it’s dealing with ongoing perceptions that they are, because of their past, forever tagged as “criminal” and subjected to a status that is somewhat less than human.

Roberto and I had never met before, but neither that—nor the prison regulations against physical contact with visitors—kept him from giving me a bone-crushing hug.

“I’m so thankful you are here,” Roberto said, towering over me while a grin stretched across his face.

The following article originally appeared on the Justice Fellowship website.

Restorative justice works. Its principles are effective in facilitating individual change and impeding the cycle of crime whenever they are applied. However, it is helpful to understand what root issue restorative justice really helps to treat and why it’s a better response to harm in our society.

Today there are approximately 2.7 million children with a mom or dad behind bars in this country. There’s no easy way to tell who these boys and girls are. They are all over the country, in busy cities and sleepy towns, in gated communities and run-down projects.

It wasn’t long before Chris found himself snowballing into an eight-year lie that would land him on the other side of the prison bars and, at the same time, propel him into a journey toward spiritual freedom.

Dr. Nance is on a mission to reach out to prisoners' children, thousands of whom live near her in Illinois’s Cook County.

Restoration Partners give monthly to bring life-changing prison ministry programs to incarcerated men and women across the country.

JOIN NOW