The following post originally appeared on the Justice Fellowship website.

With the amount of talk about recidivism, there is very little focus on people who do not commit another offense after their release. It is assumed that everyone who committed an offense poses a high threat of committing another one. But what if that assumption is incorrect?

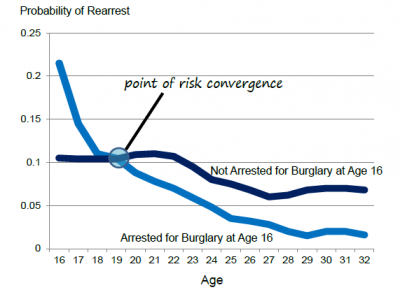

A new report commissioned by Justice Fellowship finds that many people who committed crimes reach a point where their likelihood of committing another offense is equal to that of the general population. This idea, called “Risk Convergence,” states that formerly incarcerated individuals who do not reoffend over a certain amount of time return to the same risk as the general population.

The report describes three variables that affect the risk convergence timeline for a specific person who committed an offense. The first variable is the age of the person who committed the offense. The younger the individual, the longer it takes to reach a point of risk convergence. A 21-year-old who commits the same crime as a 35-year-old will take longer to have their risk of reoffending converge with the general population. The second variable is if violence is involved with the offense. When someone commits a violent crime, it takes longer for their risk level to come down. The third variable is whether it was a first offense. People who commit multiple offenses may take much longer to reach risk convergence.

An example can help demonstrate the concept. The graph below shows the probability of arrest for someone who committed a burglary at age 16 and the probability for an average member of society. Within four years, the risks become the same.

Why does risk convergence matter? It matters because we should treat people according to the risk they pose to society. The employment risk of hiring 100 23-year-olds who committed burglary at age 16 is the same as hiring 100 randomly assigned 23-year-olds. While the data says the risks converge, policy continues to deny closure to people who once committed an offense. Their offense follows them around, despite the fact that they have successfully reintegrated into society.

When people reenter society, we should try to put them in a position where they can succeed. Delaying the restoration of rights blocks someone’s ability to fully return to society. Blocking people’s ability to work because of their past makes it hard for them to return to an honest way of living. Whenever individuals start to move beyond their offense, societal restrictions remind them that they cannot move on. The system has reached a Jean Valjean scenario where people do not accept a changed person, but continually look to what was done in the past.

We need to stop letting one offense define the life of someone who commited an offense. If formerly incarcerated men and women reach the point where they have demonstrated a changed mindset, society needs to stop forcing that individual to continually pay for that one mistake for the reste of their lives. Bringing closure is an important principle in restorative justice and is one that our culture needs to begin to embrace.

Instead of reminding a person of his or her prior offense, the criminal justice system should seek to restore all parties to the dignity of life before the crime was committed. This concept is called “restorative justice.” The goal of restorative justice is not to simply punish an individual indefinitely. The goal is to help the millions of men and women return as valued members of society. When an individual reaches risk convergence, the focus should be on assisting them. By limiting someone’s educational, housing, food, and voting rights, society continues to hold a prior offense over the individual’s head.