-

THE GENTLE GIANT WITH HELPING HANDS

After God rescued him from a self-destructive life of crime, Carmelo committed his life to helping prisoners and their families

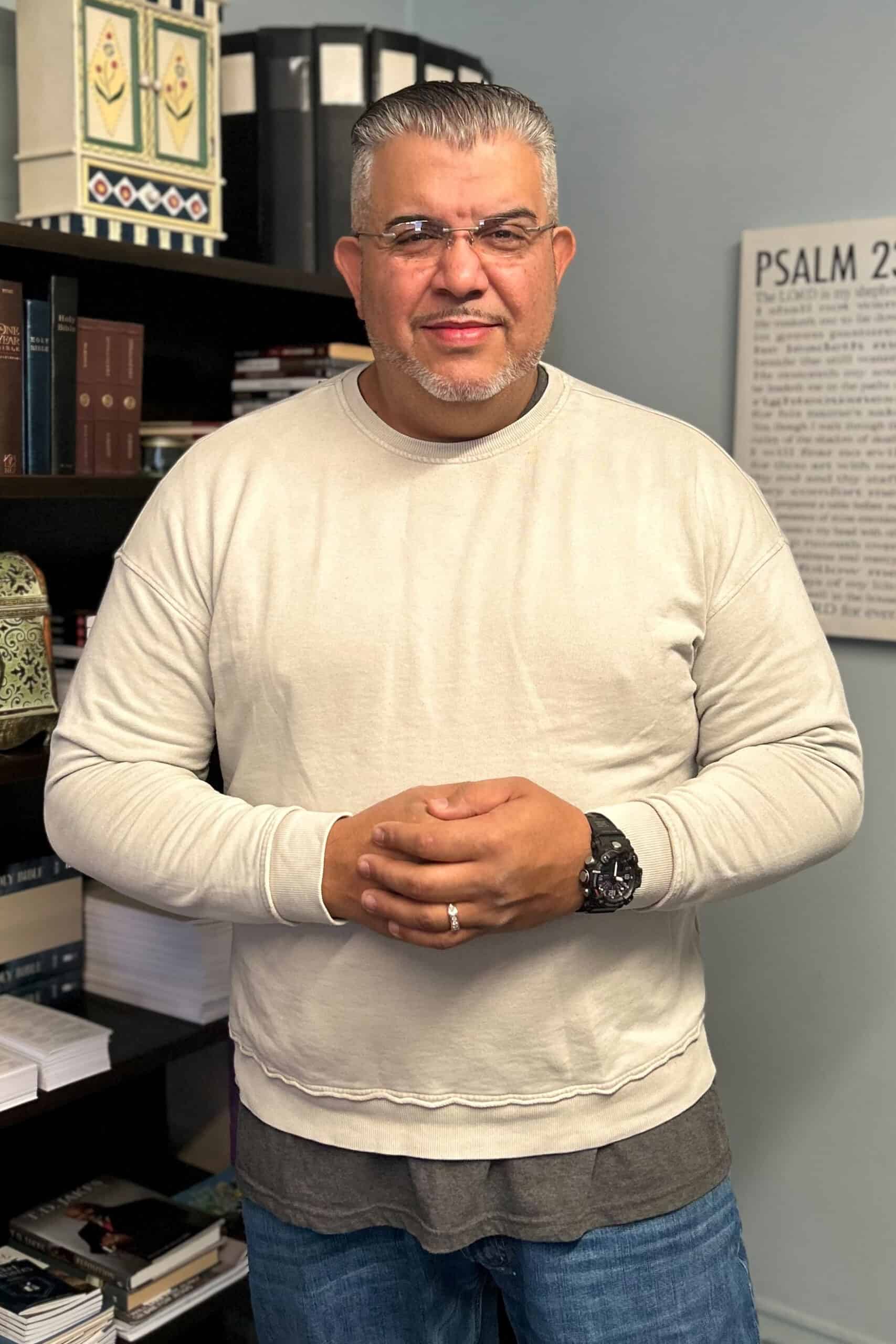

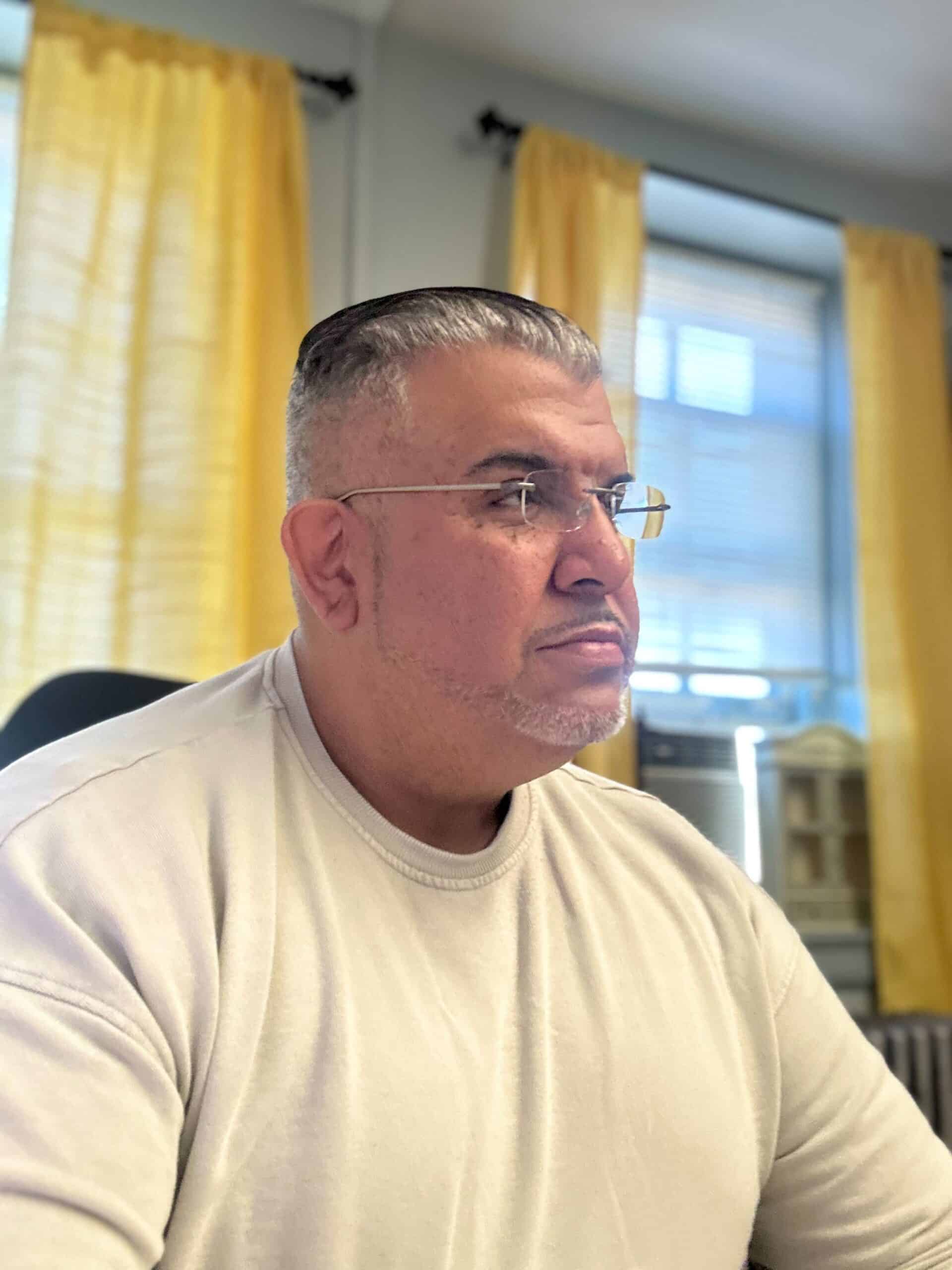

As he walks through Philadelphia’s prison halls, Carmelo has a physical presence that immediately draws attention. Standing 6 feet, 6 inches tall and weighing 330 pounds, the director of chaplaincy for the Philadelphia Department of Prisons has a stature that could easily be intimidating. However, he goes out of his way to make those around him feel comfortable, especially the prisoners whose spiritual welfare he is responsible for.

A GENTLE GIANT

Carmelo oversees religious, restorative, and transitional services for thousands of men and women housed in Philadelphia’s four correctional facilities. Although he towers over most of the people he interacts with, Carmelo exudes the calm demeanor of a gentle giant. He is also careful to wear his badge on his hip rather than on his chest, knowing that the sight of a badge makes many of those he serves defensive.

“The minute they see a uniform and a badge, it forms a shutter,” he says. “It's like closing the curtain, closing the gate. They don't want to talk to you.”

Along with his non-threatening disposition, Carmelo tries to connect with the residents by asking about their families.

THE POSTCARD THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

“There's no bigger soft spot than your children,” he says.

While ministering to incarcerated parents, Carmelo encourages parents who may have given up on connecting with their children to sign up for Prison Fellowship Angel Tree®, a program that provides Christmas gifts to kids in the name of their mom or dad in prison, plus other opportunities, like summer camps, throughout the year. Carmelo is passionate about the hope that Angel Tree can bring families because he knows what it feels like to be both an incarcerated dad and a child with an absent parent.

Two decades ago, long before he became a chaplain, Carmelo was a young father in prison facing a potential life sentence. After years of running a major drug trafficking enterprise in Philadelphia and a lengthy pursuit by federal authorities, he was finally arrested.

“I remember the first postcard that I got [in prison] was from my daughter,” Carmelo says. “She traced her hand in it, and she said, ‘Dad, I miss you. I want you to come home,’ and that's when it hit me. In my cell, I buckled to my knees and sobbed.”

Carmelo made a vow that day to be the best father he could be. Until that point, lavishing his daughter with gifts was the only way he knew how to express his love. Carmelo didn’t realize that what she valued the most was to have a relationship with him.

“She really wanted to spend more time with me,” he says. “I'm coming from a home where there's no father, so I'm not taught this.”

Indeed, Carmelo’s upbringing didn’t prepare him for fatherhood, but it did prepare him for a life of crime.

GROWING UP IN A 'WAR ZONE'

In the 1970s, the South Bronx in New York City resembled a war zone filled with abandoned buildings, shuttered businesses, uncollected garbage, and daily fires. Rampant crime, gang violence, and widespread illegal drug use also plagued the area. This near-dystopian environment is where Carmelo spent his childhood.

“There were a lot of veterans coming back home from Vietnam that were heroin addicts,” he recalls, “so heroin was dominating the streets.”

Carmelo’s father, like many residents of the Bronx, was from Puerto Rico. He sold drugs from the back of a neighborhood bodega and also struggled with addiction.

“When he would get high, [he became] a very violent person,” Carmelo recalls. “Every now and then, we [kids] would get beat, but it was mostly Mom.”

THE PAIN OF POVERTY

This cycle of abuse continued until Carmelo’s parents separated and his father left the house. Although this separation brought relief from the violence, it also resulted in Carmelo’s family collapsing into extreme poverty. Carmelo’s mother struggled to provide for her children, often surviving on the charity of neighbors.

Carmelo’s dad showed no interest in continuing a relationship with his son, even though he still lived in the Bronx. As he entered his teenage years, Carmelo was consumed with anger at his father’s abandonment and increasingly frustrated with being poor.

"I had the worn-out sneakers, the worn-out clothes," he says. "I was always being made fun of. It was rough. When you grow up [like this], the streets will give you a good reason to go out there and chase money."

'In my cell, I buckled to my knees and sobbed.'

—Carmelo

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

Carmelo soon decided that crime was the quickest way out of poverty. He began robbing local stores with a BB gun, later graduating to using real firearms and committing bigger crimes. In the mid-1980s, Carmelo started selling drugs. This was the time when crack cocaine was introduced to the area, leading to an explosion of addiction in the Bronx, where drug use was already widespread.

"What I saw that drug do to people just left me dumbfounded," he says. "I literally had guys I grew up with, I had their parents coming to me to buy drugs."

At 18, Carmelo had established himself as a significant player in the neighborhood crime scene. He made new connections who introduced him to the world of white-collar crime. He began making large amounts of money, but the risk of violence and death was always around the corner.

Carmelo got deeper into drug trafficking after marrying a Colombian woman whose brothers imported illegal substances on a massive scale. Working with his in-laws, Carmelo became a major distributor of narcotics in Philadelphia, where he ended up relocating his operation.

BECOMING A FATHER

His wife gave birth to a daughter during this time, fulfilling a lifelong dream of Carmelo's.

"That was always my dream, to have a family and a wife and a house," he says.

Despite this desire, Carmelo didn't know how to be a faithful husband or a good father. He was constantly hustling between New York and Philly. He would visit his daughter on weekends, bringing her hundreds of dollars' worth of toys, but neglected to spend any time with her. It wasn't until he was incarcerated years later that Carmelo understood how much he had taken for granted.

'I literally had guys I grew up with, I had their parents coming to me to buy drugs.'

—Carmelo

DIESEL THERAPY

Carmelo's criminal enterprise came crashing down one night when federal agents swarmed his house and arrested him. Even though he was to be detained in New York City, the police took him on an uncomfortable six-day journey, stopping at correctional facilities across the country. This process, known as "diesel therapy," was physically exhausting but spiritually enlightening for Carmelo.

At one stop, his cellmate told him that the one thing he wanted was a Bible. Later, during a bus ride, Carmelo overheard two Puerto Rican detainees behind him talking about Jesus. Carmelo's heart stirred as he listened to the men discuss their faith in Christ, and he struck up a conversation with one of them.

"I said, 'Man, can you pray for me? How do I go about this?'" Carmelo recalls. "And he was like, 'Look, say this prayer with me. It's a prayer of reconciliation.'"

FELLOWSHIP AND FREEDOM

Carmelo committed his life to Christ that day. By the time he arrived at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn, he was eager to get involved in the facility's Christian community. He began attending church services and prayer meetings with a core group of men who were also awaiting trial and sentencing.

Carmelo was arrested shortly after Father's Day, and it was during this season of spiritual growth that he received the postcard from his daughter that broke his heart. From that moment, he committed to becoming a better father and began to pray that he could get out and see his daughter again.

After nearly two years of detention, Carmelo was surprised to receive a merciful sentencing that required only four additional months of incarceration. His prison prayer partners broke out into rejoicing when they heard the news. Carmelo would soon return home as a changed man.

FRUITFUL MINISTRY

After his release, Carmelo quickly looked for opportunities to share his faith with others. Although he struggled to find a job, he kept busy by joining a group of evangelists who would preach on street corners in Philadelphia.

"Parole was requiring me to get a job, but everywhere I went, they would turn me down because of my history," Carmelo says. "I would do little odd jobs just to get by during the week, but I was really focused on preaching in the streets."

Although he was happy to share the Gospel anywhere, Carmelo longed to speak to people in prison. Eventually, a member of his street preaching group introduced him to a prison chaplain, who gave him his first opportunity to minister behind bars. Carmelo began volunteering regularly to preach to the Spanish-speaking population in a Philadelphia prison. His ability to also preach in English soon led to a diverse, growing group of prisoners attending his meetings.

BECOMING A CHAPLAIN

This fruitful ministry soon caught the attention of the director of chaplaincy at the Philadelphia Department of Prisons, who offered Carmelo a job as a chaplain. Carmelo was shocked. He had been certain that his criminal record would prevent him from ever serving in such a role.

"I was like, 'So I'm going to get paid for this? Like, this is my job now?'" Carmelo asked in disbelief.

Carmelo served as the chaplain for Hispanic prisoners for many years and eventually took over as director of chaplaincy when his boss retired. In this current role, he is focused on supporting his staff and ministering to the spiritual needs of over 7,000 prisoners.

Prison Fellowship Angel Tree is one of the tools that Carmelo uses to encourage prisoners to build positive relationships with their families. He also goes above and beyond helping parents register their children and gets personally involved in purchasing and delivering gifts to dozens of children every December.

“When Christmas comes around, if you walk into my house, you’d think you're in Santa's workshop,” he says.

LOVE IN ACTION

On his own time, Carmelo helps the families of prisoners with other needs beyond Christmas. He works with Philadelphia area food banks to supply groceries to the families of prisoners who are facing food insecurity.

“Whenever someone here says, ‘I don't have food in my house,’… I end up at their house knocking with four, five, six, seven, eight boxes of food from one of the pantries and maybe some of the stuff that I might have bought that the pantry can't offer … milk, bread, eggs, whatever.”

This personal outreach has made a significant impact on the people Carmelo ministers to. He says that many prisoners have expressed a desire to change their lives after they see the help he has given to their families.

"Disregarding ethnicity and religion, we're looking at them as people, as human beings in need," he says. "Just by doing that, some of these guys in here are impacted and provoked to change. They're like, … ‘My so-called friends didn't go to my house … but you guys did. And you guys don't even know me.’ That's love.”

STARTING A NEW CHAPTER

After his release from prison, Carmelo remarried, became a father to a stepson, and then had three more children. He is now a father of five, including his older daughter, and he greatly enjoys being involved in his children's lives. He talks to his kids about his past struggles and encourages them to make positive life choices. As a chaplain, Carmelo uses his platform to encourage incarcerated parents to be similarly honest with their children.

“I always tell everyone to do their best and not allow their children to inherit their past,” he says. “Make them aware of your mistakes, but also, make them more aware of your comeback … You made a mistake, and you might have fallen, but you got back up.”

'Make your kids aware of your mistakes, but also, make them more aware of your comeback.'

-Carmelo