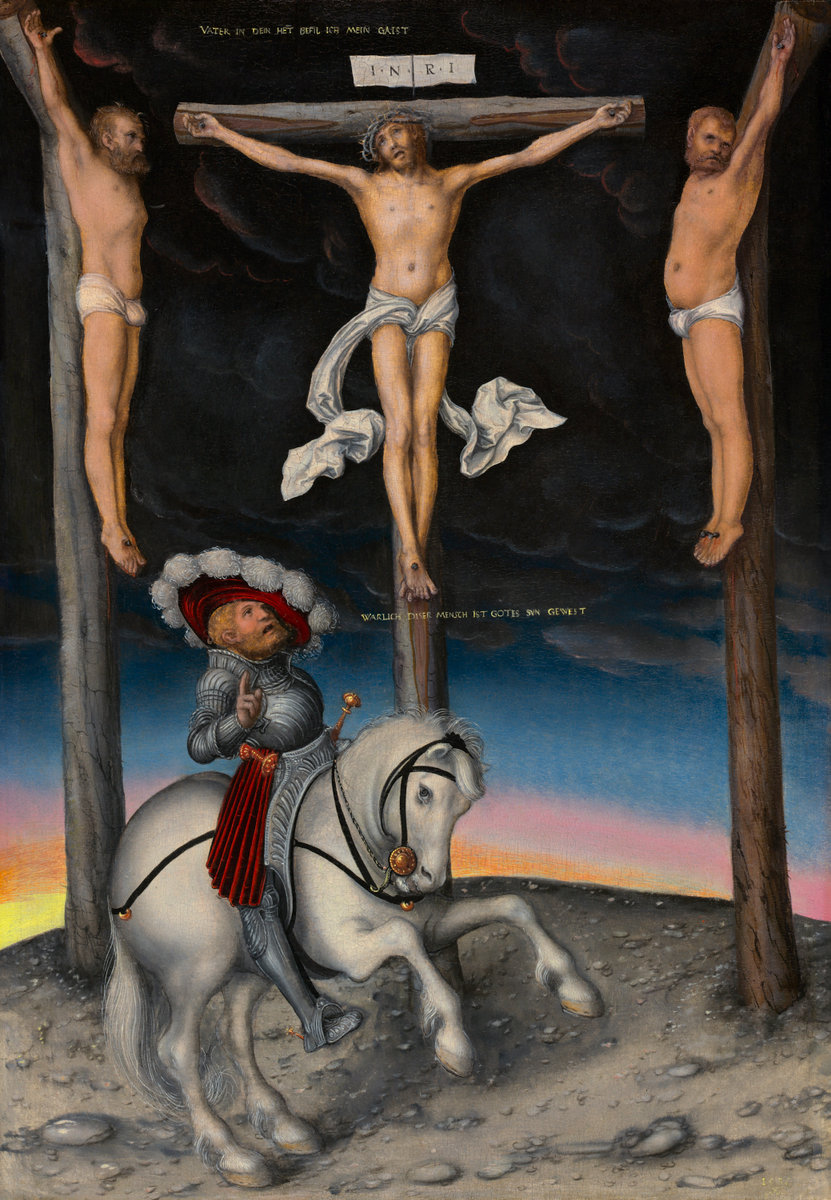

Lucas Cranach the Elder (German, 1472 – 1553 ), The Crucifixion with the Converted Centurion, 1536, oil on panel, Samuel H. Kress Collection (Courtesy National Gallery of Art) (Click on image to expand.)

The National Gallery of Art, carved out of a quarry’s worth of marble, stands on the edge of the National Mall. Inside, one finds masterpieces representing many styles, centuries, and artistic subjects. But on my most recent visit there, I looked carefully for artwork depicting prisons or prisoners. Though prisons are ubiquitous in modern societies – and have been for a few centuries – I found only one artistic representation of a prisoner: Christ being nailed to the cross.

If one out of every 34 American adults is in prison, on probation, or on parole, and if millions of children are affected by parental incarceration, why is this topic so often absent from our cultural conversations? How did 2.2 million people become invisible?

Prison is hard to talk about. It’s easy to push prison to the periphery of our public consciousness because, well, it’s awkward. Our sky-high incarceration rates are a magnifying class for our collective shortcomings, and if we want to talk seriously about prison, we must also talk about structural racism. We must talk about poverty. We must talk about failing schools, broken families, and divided marriages. We must acknowledge that we are all just as depraved as those locked away in cells. Frankly, we don’t know where to begin these difficult conversations, and it’s easier not to try.

Prison is hard to look at. Daily life is difficult enough. We have stressful jobs, family obligations, bills to pay, health problems to navigate … Who wants to spend extra time meditating on the harsh realities of prison life? Behind dull, grey prison walls and sharp concertina wire, there is a startling concentration of loneliness, violence, rape, shame, and addiction. Prisons hold some of the ugliest parts of human life, and we, who already have too little beauty in our lives, find it easier to avert our eyes and fill our museums with more pleasing pictures.

We do see some representations of prisoners in movies and television shows, but most are polarizing distortions that engender greater fear and misunderstanding. So where do we look? To Jesus.

He stopped and looked when others rushed by. He got beyond the monstrous stereotypes to see real people made in the image of God. Jesus challenges us to do the same.

At the National Gallery, the picture of the crucified Christ shows not one prisoner, but three. Christ is at the center, and beside him hang two criminals condemned to die. Christ takes on their ugliness and shame and suffers with them, dying for their sins and the sins of all humanity. And then He offers salvation to the one who will trust him.