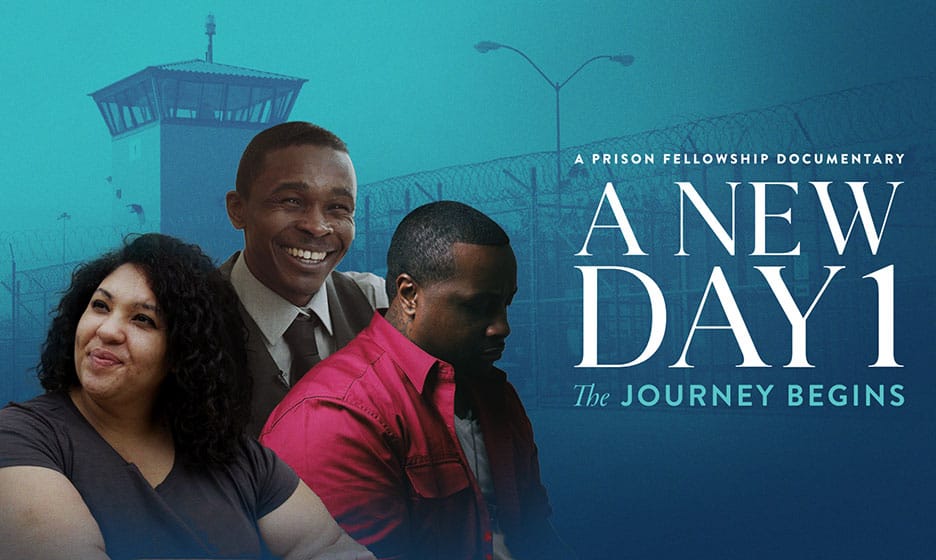

The Journey Begins

A New Day 1, an original film produced by Prison Fellowship®, documents the stories of three people returning home from prison. We sat down with some members of the production team—Topher Hall, Drew Darby, Chad Prince, and Emily Andrews—for a behind-the-scenes look at what they learned along the way.

Prison Fellowship: What do you think it was like for Hajee, Alona, and Jason to be followed by a film crew during such a transitional time in their lives?

Topher Hall: I think it spanned the gamut from fun and exciting to pretty annoying. While there were times [when] it was fun for them to have a crew around, I know that kind of vulnerability wore on them a bit. Their focus was on their next steps, not us. We were just grateful for their sharing with us during such a turbulent time.

Drew Darby: Part of me worried that our film crew would somehow impact the truth and authenticity of the stories. For example, if we bought a storyteller a meal or gave them a ride to work, could something as little as that alter their path? I have so much respect for each of the storytellers for allowing us into their lives. For them to not know where they were headed in life, but still commit to checking in with us and allowing cameras into their homes and family spaces, took a lot of courage.

Chad Prince: I was curious if our presence could point towards how important it is to have people supporting you and following your progress. I think that's key, although to be followed around by a video crew can be both intimidating and kind of flattering.

What did all three of the storytellers have in common? What were some of the challenges they faced?

Topher: They all hit the ground running. Hajee surprised me the most by getting a business license and making sales off his paintings so fast after release. The guy had orders piling up. Jason had a lot of creative power too and started making and sharing music when he got out. There's a zeal for life that comes with that entrepreneurial and creative spirit.

As far as challenges go, the variation of state laws and procedures surprised me—the role that geography plays in making it harder or easier to get set up as a productive citizen after prison.

They each faced the mundane barriers—getting their driver's license, reporting to [parole officers], doing paperwork, paying fines. Alona probably had the most red tape and practical barriers in her reentry. Getting a car and permission to drive was impossible in the near term but basically required for her job. She'd been spending more money just getting to work through Lyft than she'd earned. It was almost a wash. Talk about demoralizing.

On the other hand, Hajee had a paper license and was placed on a Virginia program that allowed for fewer check-ins and less paperwork with his PO [parole officer]. I'm convinced this made all the difference for him.

Emily Andrews: Alona had some experience with cosmetology, and she had hoped to continue down that path when she got out. She kept saying she didn't want to go back to working fast food. But her cosmetology opportunities were postponed due to COVID-19, so she took what she could get to support herself and her kids. And beyond that, she got overwhelmed just learning how to use her new phone. That’s often the case for people returning home.

They have so much to re-learn.

Drew: From my perspective, consistent employment and dependable housing were the building blocks that created stability. It wasn’t just a matter of "find a job you love," but more of a necessity to find a job that could accommodate some of the restrictions of being a returning citizen. Then, we saw one storyteller lose their housing. In many ways, that started a downward spiral.

What was it like to watch them face hurdles throughout this project?

Chad: I talked to Hajee a lot [off camera]. When he would tell me about the challenges, I would try to give godly advice and tell him I was proud of him. It was really rewarding to come alongside them in a way. They were all just trying to do the next right thing.

Topher: Honestly, it was a weird experience for me. I think each of these storytellers would agree we became friends over time. Yet, I was still in charge of objectively documenting their experience. Which, in a way, meant I wasn't here to help. That's weird, right? I certainly was there as a friend as best I could. I listened, I cared, I offered appropriate advice given my limited purview, but I had to be measured. Didn't want to offer advice that would complicate things for them. It was just hard to be on the sidelines as things became tough.

Drew: One day we sat down to lunch with Jason, and he got a job rejection email. He read the email aloud, and at that moment, it hit us: this was the same job he'd been describing to us earlier that day. He'd been through a long, drawn-out process of paperwork and interviews. Right at that moment, his hard work was erased, and he was back to square one. Credit to Jason, though—he took it in stride and was immediately thinking about his next steps. He never wavered in his conviction that he would find the right place to work.

When you look at the pillars of reentry, were there any you felt like were "make or break"? That they couldn't survive without?

Topher: Transportation really paved the way for opportunity. I didn't pay much attention to it when we started out, but it's a game changer. If you can't go anywhere without paying, it's a really big setback.

Family guided Jason to a better next step in a better geographic area, and his hustle to find jobs meant stability, in his case. Church played a big part in his support network, too. In-prison programming gave Hajee some skills I'm convinced made him a better entrepreneur. And Alona had the support of friends and housing.

I honestly can't say one thing matters more than the others—it's the sum of all parts. You need a blend of family and/or friends, employment, housing, church or support network, and something else. Maybe I'd call it purpose, or an understanding of one's purpose. Not necessarily a job, or a calling, but a grasp (even a loose grasp) on a God-given, innate purpose. I saw a glimpse of the effect that knowing one's purpose can have; that feeling of confidence as a spiritual being. There is work we need to do to remove the barriers of reentry, and we all have a part to play in that. But there's also a mental and spiritual battle that people have to face within when they're recalibrating after they've veered off.

Why is it important to put a human face to the reentry process?

Topher: Many of us viewing these stories haven't been living in prison for periods of time. But what we're talking about here are habits, direction, goals, family, and friends. All of these big-picture struggles couched in the mundane—who can't relate to finding the right direction for your life, choosing the right people in your life, and creating empowering habits? All while dealing with things breaking, people letting you down, paperwork, and waiting on hold for customer service. Their stories are within the criminal justice system, and the pressure is amplified. Their decisions following release have more weight than our everyday life decisions.

Drew: If you've seen the film, you know that not all of the stories wrap up with a perfect bow on top. There are loose ends and questions of "what next?" That is something on a basic level that we can all connect with.

You've spent a lot of time interviewing and filming men and women in prison, sharing their stories. How was this project different for you?

Topher: In a word, relationship. I formed relationships with the people we worked with. That isn't always possible with some of the more in-and-out storytelling trips we do. While we love to keep up with people, we also are tasked with sharing a lot of great stories. I don't often get to become this familiar with people. I loved it.

Drew: When we met our storytellers, we didn't know where the next year would take them. We couldn't have predicted a global health crisis. We didn't know who would get a job where. For some, we didn't even know a release date until it was just about to happen, and we had to scramble to cover the event. This film helped me appreciate the fact that while our film was complicated to coordinate, their life circumstances were even more complex.

Emily: It's kind of rare that I get to follow someone's story as closely as I followed Alona's. I met her behind bars in Oklahoma a few years ago, and later I attended her Prison Fellowship Academy® graduation. I got to see her apartment at the transitional home and meet her three kids. We talked biweekly for several months so I could keep up with her journey, for the film. It's really special to have a chance to build that rapport with someone and to root for them along the journey.

Has anything changed about your perspective of people with a criminal record after doing this/similar projects?

Chad: I've been through reentry myself. So, in some ways, I knew the reentry process. But this [filming] process reminded me how much pressure there is. We should give returning citizens guidelines, hold them accountable, but remember that they're human, too. They need encouragement. They are under a lot of pressure to "make it," and putting them under unnecessary pressure can do more harm than good.

Drew: While making this film and producing others about returning citizens, I am reminded again and again that while a criminal record may be a part of someone's story, it never has to define the individual's potential.

Emily: The idea that people with a criminal record are "other" is still really pervasive in culture. This project reminded me how important it is to humanize every person's story. We all get overwhelmed. We all have coping mechanisms. I felt really honored that they would share with us so openly. It can be painful to unpack the most difficult parts of your story for someone, even when there isn't a camera on you. There's something powerful and good about sharing those things out loud. But it can also be emotionally taxing, and this project deepened my respect for that.

What do you hope people walk away with after seeing this film?

Chad: I'd hope people will see returning citizens as people who've made a mistake and changed and grown to be an asset to society. And it's really important to have a second chance, community support, family support, a job, and somebody that knows you and your struggle and can hold you accountable.

Drew: My hope for A New Day 1 is that it offers a very realistic, accessible look into what a person experiences in the first year after being released from prison. These are not one-in-a-million stories—each of these storytellers shares a similar experience to millions of other Americans. I hope that watching this film offers viewers a perspective into a segment of society that we often don't talk about or [we] tiptoe around.

Emily: It's sad to say, but a lot of people don't care about an issue until it affects them personally. Film has a way of drawing people in and making them feel proximate, in a way, to something that matters. It's important to get close to hard things. Momentary comfort isn't worth more than someone else's chance to be seen and heard.

Topher: I want people to love the three highlighted people in this film and realize they can love others in similar situations. I hope people who see this film will be more inclined to lend a helping hand, and if we can, move needles on state and federal policies that create a more ideal environment for making good on a second chance.

WITNESS THE JOURNEY

Watch the documentary to witness Jason, Hajee, and Alona’s stories, and then download this free discussion guide to further explore the topics and issues brought out in the film.

DID YOU ENJOY THIS ARTICLE?

Make sure you don' t miss out on any of our helpful articles and incredible transformation stories! Sign up to receive our weekly newsletter, and you' ll get great content delivered directly to your inbox.

Your privacy is safe with us. We will never sell, trade, or share your personal information.